Robert Frank: An interview with Gerald Fox

British film director Gerald Fox has produced many portraits of artists, photographers in particular. But Robert Frank, while being an artist who opens up about his own life through his work, was nonetheless a man of mystery, complicated, withdrawn from the world. Gerald Fox revisits the story of this film, just like Frank himself, with its ups and downs, but above all exciting and human.

Emmanuel Bacquet: The first thing that maybe intrigues me about your film is the way you met and convinced Robert Frank. I mean, he was a kind of a hermit, how could he become so trusting to make this film with you?

Gerald Fox: Yes. It's strange, because it began at the time Robert Frank was doing a big retrospective show at the Tate Museum, in London.

The curator and director of the Tate was Vicente Todoli.

I approached him and asked, "Is there any chance that Robert Frank would do a film? Because everything I've read about Frank is that he doesn't give interviews, never talks".

He said: "He lives like as a hermit in Mabou, in Nova Scotia. And there is no way you would ever make a film".

But Vicente said he could try to convince him. So he sent him one of my films, which is about Klaus Rosenberg. And then I heard nothing. And one day the phone in my office rang. This was early era before email and everything.

And the guy says, "Hello, it's Robert Frank here". And I'm like, "Oh, my God". He said, "I watched your film on Klaus Rosenberg - I liked him. I knew him and I liked your film". And then he said, "Maybe we can do something similar".

But he said, "I'm not like him. I am not an intellectual". I answer "It doesn't matter". "Also" he said, "I do nothing. I sit every day and I look out of the window. Occasionally, I light the fire, but effectively, that is nothing. But if you want to film nothing, come and film". So I said, “Okay" and he pointed out "I want to work with the creativity of the director. That's the main thing".

I said, "Well, I'll try and be creative".

Strange thing, I didn't have to convince the people to give me the money quickly, and all of the rest of it, to get over there. When I got over there, it was a little bit more difficult because he was friendly and everything. But also you could see that he's moody, up and down and whatever. And it was going quite well. The first day, I asked some good questions, as he seemed quite happy.

And then comes the next day, and I wanted to take him to places, like going back to Coney Island with him, and go on the bus with him, go to all of the places where he used to photograph. And I tried to be very creative, and I bought some black and white film, so it could mirror the look of the times when he photographed from black and white films. And he still was very kind. But the trouble was it was a very wet and rainy day, and it was too dark for the film I had. He comes to me and said, "I saw one roll of black and white film from 1953. Do you think it's good enough? I think it might be out of date". He started to get a little bit concerned by the whole thing and the way we were doing it. And finally, he disappeared into his study and didn't come out. Then his wife suddenly came around, June, his lovely artist wife. She said "I talked to Robert, and Robert said we need to get going, you need to hurry up. The main thing Robert says is you mustn't be scared of him". I said "Well, I'm not scared of him". She answered "Well, you bloody well should be, everybody's scared of him." At this point, I realised you're dealing with a guy who was up and down. That’s the moment he exploded on me, and it's in the film!

EB: I remember, yes.

GF: And he suddenly goes, "What's behind this? This is no good, I can't do this. It's all rubbish". And so it was very much up and down… up and down. And I had to, as you say, get across, to get him to reveal both his life story and the way he worked as a photographer. And I didn't think either of those things were going to be that easy. The life story was published. He had lost both his children and that was a part of his life that he reflected in his photography and filmmaking. So it was important to me that we try to look into that. If it had nothing connected to his work, I wouldn't have done it. But I felt like we were telling the life story in the way that the art and life, photography and his life interweave.

Then you need to be able to explore that, as well as looking at The Americans and all the early stuff, his wonderful photographs, you needed to look at that. So he said to me at one point, "The one thing I told everybody, and I'm going to be totally honest with you. So if you ask me a question, I will answer honestly", which was an amazing thing.

So I said, "Okay. Well, then I'm going to try and ask you". So I asked him about his son and the way he reflected that, and then it's his daughter. And he did open up. And by asking things in a nice way and trying to get him out on the street when he was doing it, it was quite clear he didn't want to do that kind of formal interview. But if, when you're walking around with him, you throw questions and he's being honest, he will answer. Later, when I think he did realize how much he had revealed, there were problems with it. And he told the curator of the Vintage Photography Museum who was a friend. He told me that he'd said, "I said too much". That he had opened up too much, that he didn't really want to put all that stuff on record. But I think he wasn't an easy character. He was almost somebody who you would say was a person who has ups and downs, almost on the spectrum.

EB: After being through everything he lived with his son and daughter, we can understand he's a bit disillusioned.

GF: Yes, exactly. Even as a person, he was not an easy man, and he had a temper as you could see. You had to be on skates just to try and find the best way to draw him out and to tell us the story. And then also, I wanted to show the way in which he took his photographs. So I thought to gain his trust that we'd go to somewhere like Coney Island, take him back to places where he photographed. Let him walk around and let him show you how he photographs, how discreet he was, how he chats to people, how he looks around and he sees what he sees, and he'll use that trick right. He said, "That's what I would take a photograph of.»

EB: Yes, the sequence with the girl with the towel for example.

GF: Exactly. So the film was an attempt to capture all that, you know I didn't have long with him, I had to do this all in a few days in New York. And then I had a few days in Nova Scotia. He just said afterwards that I nearly killed him with the amount of work I made him do. But I wanted to tell that life story, and then use his own films as a way to illustrate a lot of what he said. So you had this amazing archive of his own work that he's made (in either documentaries, personal films), as a way to visually illustrate what he was saying. So the effort was really in terms of getting him to dig deep into his life and reveal the story of an immigrant who comes to America.

For a long time he was penniless. And he also suffered because The Americans, when it first came out, was derided by the press. It wasn't a huge success. And that put him off, actually. He switched to film after that. Because I think he was very hurt by the response. Later, of course, it becomes the greatest, most influential photography work of the last years. But it certainly wasn't then.

And it certainly wasn't even when I made the film. Five years later, the Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington did the big show of The American. And suddenly, everybody's like : "Oh, my God, this is incredible work of photography".

I set out to work with the creativity of the director, of the art, and to find a way to reveal both the life story of the photographer and the photographer's exploration of life itself. How he found a way to make photographs where he didn't have to set it all up, he didn't have help, it was off the cards. That was the approach, very informal, very discreet, very moving, and that was very innovative at the time when he did it. So this is what I was trying to do in the film. And then also were all these videos he made, the way in which his own personal films played such a big role in his life.

EB: What happened after the film? I heard that there was some kind of complexity when the film was released, because at first he didn't want it to be shown.

GF: What happened was, in the beginning, it was shown at the Tate Gallery, during his retrospective outside the gallery. Everybody was watching it. That was a shorter version of the one you have. It was like a 50-minute television version, and it played on the television in Britain. That was a big success.

But then I took it to a few film festivals, the longer one, the one that you're going to show, and then he hears about it.And one day he calls me and says, "I'm really, very angry with you". And he's screaming to me and shouting, "You have no right to show the film", and "I only gave you the rights for one month". I never really understood why. And then he said, "You can't show the film at all", at first. "Not even in film festivals".

That's how the problem started. Everybody wanted to show the film. People wanted to show it in the cinemas in America. He said, "No, you can't show it anywhere". And I was like, "Robert, you can't do that".

He finally said, "Well, at maximum three festivals a year, that's it. And no more". And the joke was that that was exactly the same thing with the Rolling Stones with Cocksucker Blues. He made this film about the Rolling Stones, and they didn't want the film to be seen, because they felt that it would hamper their ability to come to America, because it showed underage on the airplane, and drug taking and all of this. So they said to him, in the end, he could show it three times a year, but he had to be present at the screenings, and all that sort of thing. It was like he was enacting the Cocksucker Blues on me as a revenge or something.

EB: It looks like!

GF: Crazy! And that went on for a very long time. I couldn't show it, except special screenings. And occasionally, even he would ask me to show it like at the Metropolitan Museum, when his thing about The Americans was showing. He wanted to show the film. So it wasn't like he really didn't like it. Either it was because he felt he said too much, and he didn't want it to be out there. He liked his solitary, quiet life. He didn't want the private world of his son's death to be so public, particularly in America. Or it was because he had promised Laura Israel that they were going to make a film, maybe together, or they had started making one and he didn't want it to ruin the opportunity that he had promised her. I don't know.

EB: Laura Israel made another film with him : Don’t Blink. She was her assistant and editor on a lot of his films.

GF: Yes I met her, of course. But anyway, so once that film had come out and I looked at it, I watched it, I thought « It is so different to Leaving Home ».

And it's actually more about the films he has made than about the photographs, in a lot of ways. And he's a very different man in that film. He's like 90 something there, 90 I think by the time she made her film and he's sweeter.He's a very sweet little man, but he has not got that edge, that wrath and the way he talks and everything that he added in the film that I did with him. He was younger, I think he was 79-80 years old, at that age you still have that anger which likely has gone 10 years later.

But it's a different kind of film. So then I went back to him one day, I'd made an effort, I took him a present… First of all, I got in touch with June. She said, "Come and see him".

I hadn't seen him because I was so upset by what he did, I didn't see him for 10 years. Then we went to chat and I said, "Robert, I don't know why, but think about what you do to the film. It's a wonderful tribute to you as a photographer. It explores your photography and why you are such a great photographer". So he said, "Okay, you can show it". And then it was free to have a cinema release in America, and to be on your platform and that kind of thing. So I was lucky just in time. It came out literally in America, in the cinema only about a couple of months before he passed away sadly. He was going to come to the openings, but June said to me, "You mustn't be angry that he wouldn't let you show the film, because I don’t think he even remembers why". But The Americans grew in stature, so the film, in a way, grew with it. And when it comes out, it's now a film about somebody who is really very highly respected for that body of work.

EB: The time to release the film freely was in a way more appropriate?

GF: Maybe he knew from Cocksucker Blues : actually, Cocksucker Blues is okay, but it became so much more legendary for films, so much more influential, and the mystique of it was so great because the Rolling Stones wouldn't allow it to be seen. So it becomes, in the eye of the public, a much greater work of something than it might otherwise have been. I think maybe he felt that this film would do the same! (Laughing)

EB: Maybe he did it on purpose!

GF: Exactly.

EB: That's a great story. It must have been something really affecting for you, this period of life. It was maybe long, two or three years with the editing?

GF: Oh no. It wasn't two, three years with the editing. Because it's not one of those films, as the one with Bill Viola, which took me 10 years to make. This one was made very quickly. But sometimes, when something is made very quickly, you get an excitement and energy and things happen, like you might never get, if you're always just following somebody around with a camera.

You get a different kind of film. You probably get the more honest truth of the character. But with this, those moments, like when his wife screams, and then he screams, that and when he lost his temper with me; I could film for years with Bill Viola nothing like that happens.

Whereas for a short while with Frank, it's almost like it's a theatre for him. So he's really going to throw it around a little bit, act naughty and that kind of stuff. Then, similar with the editing, because it was a television and because it would have to be ready for the Tate, I had to edit it very quickly. In fact, the whole project was very quick, but in a sense, it was a lifetime of work for me making these films, like you saw my film with Gilbert and George. I always liked doing things with people who work with photography, even if they don't take photographs, like Gilbert and George, like Christian Boltanski. I made a film with Christian Boltanski, great job. Christian works with fan photographs: a lot of the work is with using fan photographs, and photographs in magazines, and pictures he styles, that sort of thing. Albums of photographs, the dead Swiss photographs that he found in a magazine, or these people from schools, or portraits of children who ended up in the Holocaust. So I brought, I hope even at that stage, a lot of experience on how to make a film. So even though you have a few days to work with somebody like Robert Frank, you know how to get what you need out of it to tell the story of his life.

EB: Maybe sometimes that's better to think and create in a state of emergency.

GF: Yes, sometimes. But other times, it's good to have time with people, and longer time with someone else. I'm sure for Laura Israel’s film, that she had a longer period of time, but he doesn’t have the same edginess that he had in mine. But there's no question, it's a different kind of thing.

And, actually, what I wanted to do was to try and push it to reveal what made a good photograph, or what made a good photographer. What is it, the humanity? What is the real thing that makes someone Robert Frank, or whoever a photographer of those heights to a normal photographer? A lot of it has to do with humanity and how they treat people and the way they look at the world. And that's what I was looking to make a film about photography, what makes photography good.

EB: It's a bit of what makes a good director. The way you pay attention to the other. There's something in common in the way you create something with humanity in photography and in filmmaking.

GF: Yes, definitely. Yes, for sure. That's why our aim is always to work with the artist, or the photographer, or whatever it is. And to try and bring out what it is that makes somebody humane, and artistic, and intelligent about what they do. Particularly when he was young, he was a very driven photographer in that way. He travelled the world to try to find the image. And then, it's so funny that he had to come back to America, after having gone to Spain, and France, and England, to take photographs in Paris, and in London, and then back in America. Then, when he's back in America, he looks at America through an outsider’s eyes, in a way. He finds something very powerful. And what's brilliant about The Americans is the way he edits, how he finds the right pictures within all the pictures he has taken. The way he uses the contact sheets to just spot a picture that says something, so it's about that process as well.

EB: He says in your film he was surprised that The Americans was felt like something cynical. Surprisingly he was disappointed that people can feel a caustic way of looking at things in The Americans.

GF: Yes he was looking at America at a time when there was a lot of extremes of wealth and poverty in the country, and racism. There was a darker side to America. But the critics didn't like to see that, at the time. People didn't want to be confronted by that reality. So when it comes out, people say he's a foreigner who's trying to be cynical and hateful about the country.

Later, of course, they looked at The Americans differently. It's a look at all aspects of life in America. I'm sure he was trying to give them a portrait of the country at that particular time. In the 1950s, I suppose everybody thought America was just great. He travelled, and he saw what he saw, and I think he realized that he needed to show all aspects, not just that image of America as a great nation.

EB: Thank you so much, we learned so many things! Maybe we can conclude this interview because the translator will have a lot of work. (I’m just joking)

GF: Was it too long? You can cut it through.

EB: Oh no, we won't cut!

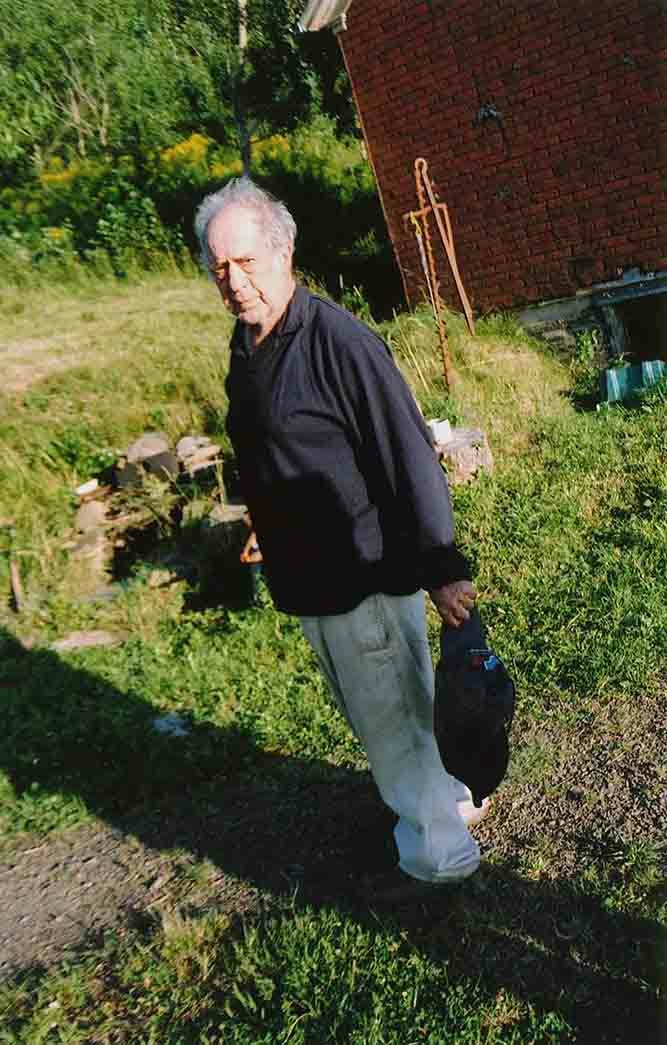

GF: It wasn't the final point I was going to make. It was a real honour in my life, now looking back, to have had that opportunity with him. Because it's a rare thing that you find a man who never succumbed to the trappings of wealth and fame. Even after he was making a lot of money from his photography. For a long time, he had no money, and then when he was starting to make money, he needed cash for his son's illness, to pay for his son's hospital and all that. So he had to sell off his archive, his rights to his own work. Then later, his gallery managed to get that back. After that, he became very wealthy. The prints started selling for phenomenal amounts of money. But he never changed his lifestyle. You look at this in the film, you know grungy, living down in the Lower East Side. He stayed true to what it means to be an artist, right through his life. Even when I went there, months before he died, he's still living in the same rough bed. They believed in the fact that an artist has to stay true to his roots and, not to poverty, but to the fact that you can't separate yourself from the world. If you want to still be a photographer, if you want to still be an artist, you have to stay true to that world. And he never succumbed in that way. It's amazing how, despite all the tragedies, he carried on working and doing his thing. He wasn’t that prolific, especially in the last years, but he was always trying to do interesting things. It was a great opportunity to spend a little time with the guy.

EB: Thank you so much Gerald, maybe we’ll soon talk again together about the film with Gilbert and George.

Notes

Robert Frank: Storylines. Tate Modern (London)

(10-28-2004 – 01-23-2005)

Leaving Home, Coming Home - A Portrait of Robert Frank, 2004, a documentary film by Gerald Fox.

Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans. National Gallery of Art (Washington)

(01/18 – 04/26/2009)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC)

(09/22/2009 – 01/03/2010)

Cocksucker Blues, 1972, a documentary film by Robert Frank.

Don’t Blink, Robert Frank, 2015, a film by Laura Israel.

This interview with Gerald Fox has been carried out shortly before Christian Boltanski died, on July 21st, 2021.

Christian Boltanski, Les Suisses morts, 1989, installation.

September 2021