The Journey of 'The Celestial Darkroom' with Film Director Nils Petter Löfstedt

In an exchange with The Darkroom Rumour, filmmaker Nils Petter Löfstedt reveals part of the moving journey behind "The Celestial Darkroom".

Through written answers to five questions, he shares the happy beginnings and emotional upheavals that shaped his cinematic tribute to Hermanson's legacy, as well as the tragic lessons he learned from it...

***

• What originally prompted you to make a documentary about Jean Hermanson? What was your relationship before starting filming?

I moved to Malmö, in the south of Sweden, in my twenties. Once in a second-hand bookshop I asked for books by him and Folke Isaksson, I knew of them. The shop owner replied "You know, Jean sits in the back, he's here." But I was too shy to talk to him.

When we finally started hanging out he wanted help with his computer and the digital processes. I asked him about everything, I watched him in his dark room. We agreed on many things, he valued what I valued. He strengthened me.

I never had a clear idea of portraying him. That was something I did just for myself, to learn about filming. And to seize the opportunity of saving his words, and our conversations. If you know how to work a camera, taking pictures, then there's never a break in work, right? Because there is always something interesting going on around you: in the street, at your neighbor's, actually in any room where people are busy, like for instance a work place. So bringing a camera to his place was obvious to me.

He didn't want me to film him at all. But he realized the value in me documenting his work processes in the dark room. He knew that this knowledge was being lost.

Jean Hermanson in his darkroom.

• Jean Hermanson passed away as you began shooting the documentary. This must have caused a real upheaval for you, both emotionally and creatively. What impact did this have on the production of the film and on the way you chose to represent his life and work?

I shut down at first. I stopped thinking of it and I stowed away everything. There wasn't a film project then, it was just our friendship. I didn't know his family. When Jean no longer was with me I was convinced that it all was over. There was nothing more to do of everything we had talked about. I went to the funeral service but I sat all alone in the back.

Then came all practical questions after Jean's death. His son and daughter contacted me. He had talked of me and the three of us decided to cooperate. We had to decide what to do with his archive. His daughter Jonna helped out in my workshop in her spare time.

I also could open up my material again, just looking at all the pictures. But it was actually my brother Johan, he had worked with film for many years then, who suggested that I should try to make a documentary about Jean Hermanson. I watched everything I had recorded and it was all new to me. I understood what Jean had told me, what he had given me, and what I needed to do with it.

Jean used to joke about a darkroom in paradise, a "celestial darkroom" where only analog photographers are allowed. Now he was there but all his pictures were still here with us.

• Were there any surprising discoveries in Jean Hermanson's archives during the making of the documentary? Are there any moments or conversations with Jean Hermanson that you regret not filming or including in the documentary?

I regret not asking him more about how he interacted with the person he took pictures of. What was his approach, how did he prefer to do it and what did he try when the relationship didn’t feel right?

And one of the most famous pictures of his – by the punch clock in the stairway – did he just capture a moment or did he stage it, perfecting the image? Such knowledge would maybe reveal more on how he worked.

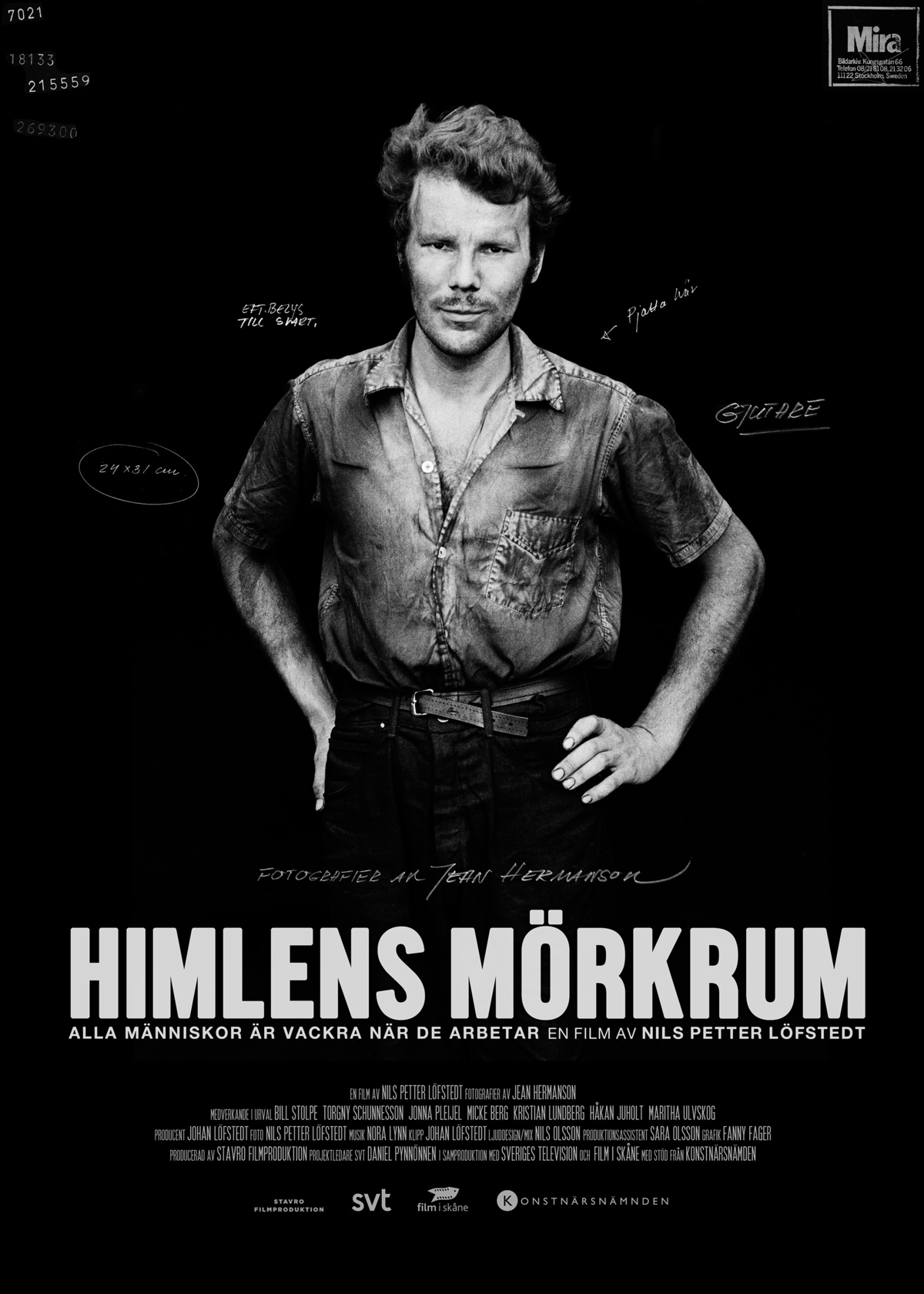

Film's original Swedish poster

• What personal or professional lesson have you taken away from this unique experience of making a film about Jean Hermanson?

Unfortunately, I feel obliged to comment on something else, a completely different, very practical issue. And quite upsetting. This is about something that happened after the making of the film.

The city of Landskrona bought the archive with a promise of taking care of it and supporting Jean’s legacy. They made grand plans of creating a national centre for photography, with Jean’s and other photographer’s archives as part of the operation. It has all been abandoned.

Initially, they kept their promise regarding Jean’s archive but I saw more and more warning signs as time went by. Now, I would call it a disaster. They kept things in an attic storage, with unsafe electrical wiring, an old sink and a water tap, no climate control – many things were placed in cardboard boxes directly on the floor. And before that, it was all kept in an unlocked area, like a hallway. It’s been moved around, tens of thousands of photo negatives and original copies. The digitization process was flawed. No registry of the prints has ever been made.

In the beginning we had something very promising, a vivid exchange, a real conversation on photography. It was a genuine cooperation. In Sweden there is no national readiness, no state agency, for taking care of photographic archives. It’s up to relatives, family and friends, to work this out. At best, there’ll be a local museum or city archive that decides to help and agree on taking responsibility. And in this case, it turned out to be a sort of treacherous solution…

• What impact would you like this documentary to have on how the public and contemporary photographers view Jean Hermanson's work?

I stand firm in my conviction that Jean’s photography is important to people. I have met so many all over Sweden who confirm this, something real happens when they see the pictures.

Luckily, our production company can keep working with Jean Hermanson’s archive. We found a real treasure a while ago, something absolutely amazing! We can now listen to the people in Jean’s portraits! He took pictures and the writer Folke Isaksson, Jean’s collaborator on these trips, did interviews together with Jean, mostly in the workers’ homes. Folke saved all the recorded interviews and we have found the archive! Hearing these voices is incredibly emotional. We are gonna travel the country making this available to anyone concerned and we are of course recounting it in a new documentary, the sequel to Celestial Darkroom.

Questions sent by email

in January 2024

by Thomas Goupille